As the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) conducts another assault in the north of Gaza, they face significant criticism from Western officials and analysts who are asking why the IDF is repeatedly going into areas they have already cleared and conducting further operations.

Critics claim this behavior reflects a flaw in operational design or is even proof that Israel’s campaign against Hamas has failed.

The flaw, however, lies in their own assumptions.

These critics are looking at IDF tactics through the lens of Western counterinsurgency (COIN), the doctrine that US and European militaries applied in the failed campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq.

In the “global war on terror,” Western tactics were to seize a chunk of territory and clear it of enemies through military force.

The plan was then to hold the territory through forward operating bases (or FOBs) and try to conduct alternative governance in those areas while providing security.

The system of FOBs meant that our enemies, embedded in the local civilian population, always knew where we were and what routes we were likely to use. They could mortar, rocket, and IED us at will.

It was a recipe for endless violence and huge numbers of casualties.

In the case of the 2023-24 Gaza war, Western critics have almost comically misunderstood what the Israeli military is trying to do.

The flaw in Western analysis is always the same: “We wouldn’t do it that way.”

Yet the IDF has absolutely no intention of using the clear-hold-build COIN tactics the West tried in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Why would it?

Those tactics were an unmitigated disaster in both campaigns, which ended in humiliating defeats at the hands of technologically inferior armies.

COIN tactics are time-consuming and costly.

They also require huge troop levels to “hold” ground, for years if not indefinitely.

Assuming Western doctrinal ratios of 1 soldier to every 40 civilians, Gaza would require an enduring deployment of 50,000 combat troops, before we even consider enabling logistics, engineers, artillery and the like.

The economic costs of mobilizing the IDF’s reservist army on an enduring basis would be astronomical.

Such tactics would also be insanely wasteful, since Israel has a safe base on the Israeli side of the Gaza border, and can therefore enjoy the luxury of only committing to intelligence-led operations at times and on grounds of their choosing — advantages that the West did not have in either Iraq or Afghanistan.

So why is the IDF repeating operations in areas that it has already cleared — for example, in the Shifa hospital, or in ongoing operations in Jabalia, which they struck from the air at the start of the conflict?

Critics call this approach “mowing the grass,” a phrase adopted in the West to describe the failure to deploy sufficient troops in Iraq or Afghanistan, leading to repeated clearances of the same areas after they were thought to have been “cleared.”

I contend that the IDF is trying something completely different, and it makes sense.

Israel’s strategic aims are defeating Hamas and securing the Gaza border with Israel to prevent a repeat of Oct. 7.

“Never again is now” isn’t just an empty slogan.

IDF operational design is built around making sure Oct. 7 can never happen again.

Absent the possibility of any enduring political solution, that is simply what success looks like.

In military terms, Hamas will not be destroyed, which means rendered totally combat ineffective.

Hamas is too numerous and too entrenched within Gaza — where every male of fighting age is a potential future Hamas fighter.

Their cellular structure makes them hard to target, and when a commander is killed, they have shown the flexibility to promote the next man up.

They are also mainly backing away from a fight in Gaza, relying on booby traps, IEDs, and small arms engagements before melting away from decisive engagements.

This makes them hard to kill.

What is possible, however, is defeating Hamas.

In Western doctrinal terms, “defeating” an enemy means reducing it to 50%-69% of its fighting strength.

As Gaza is neither a conventional war nor a counterterrorism operation in the classic sense of each, we can frame that percentage as the removal of Hamas’ ability to repeat Oct. 7.

So how does the IDF plan to achieve the aim of defeating Hamas?

Through a political solution?

Definitely not.

No one on the international stage has expressed any interest in helping with governance in Gaza.

Nor is there any evidence that these nonexistent partners would do anything other than act as human shields for Hamas, making it impossible for Israel to attack its foes when necessary.

The idea that there exists some magic device to convert any sizable number of Gazans to embrace a political alternative to Hamas that would be in any way favorable for Israel can be generously termed a fantasy.

According to polling, 2% of Gazans support an Israeli-backed administration.

The majority want Hamas back.

Israel’s war cabinet has received significant domestic and international criticism for their lack of a “day after” plan for governance in Gaza, which has been echoed in recent days by Defense Minister Yoav Gallant .

IDF planners are therefore faced with designing operations to achieve a loosely defined goal, with no clearly articulated strategic end state for the operation from their political leadership — in part perhaps because the “end state” may be unsatisfying to Western ears.

So how have they met this challenge?

If you look at what is possible, what the best version of “success” looks like, and what Israel is doing, I contend that in Gaza we are seeing a masterpiece of operational design within severe politically imposed limitations.

The IDF is not trying to clear Gaza.

With no ability to impose a political arrangement in Gaza, and a Gazan desire for continued Hamas rule, the IDF answer is: Let them have Hamas.

But the version of Hamas that Gazans will get is one heavily degraded militarily, and, most importantly, with vast swaths of their tunnels and civilian-embedded infrastructure destroyed.

In other words, the IDF aims to replace Hamas 3.0 — the version that fought three wars against Israel and then launched the brutal Oct. 7 surprise attacks — with Hamas 1.0, which took over the Gaza Strip from Fatah in June 2007.

To accomplish that end, the IDF has methodically razed what Hamas infrastructure they could find in Gaza City, Khan Yunis, and now Rafah.

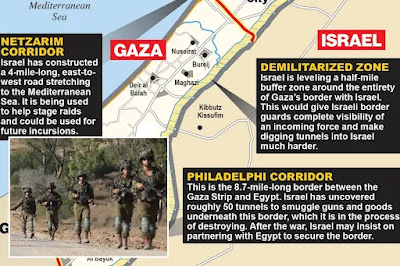

They have secured the Netzarim corridor to control freedom of movement from south to north.

It looks like they are trying to do the same thing along the Philadelphi Corridor and Gaza’s southern border with Egypt, to cut off the inflow of weapons and supplies to Hamas.

Facial recognition software in controlled areas allows the IDF to stop known Hamas commanders from moving around.

This posture also allows the IDF to strike when concentrations of Hamas are identified, to degrade their manpower, and then withdraw again: And that is what we saw at Shifa hospital and are seeing now in Jabalia.

At the same time, the IDF has methodically destroyed buildings to create a 1-kilometer buffer zone around the Gaza border — a measure that if enforced would indeed prevent a repeat of Oct. 7.

If Israel has its way, nobody in Gaza is getting anywhere near the border again.

However, whether Washington will come down against this policy remains to be seen, which is why for Israel, the key strategic goal in Gaza is arguably to limit as much as possible the internationalization of the Strip through fantastical plans for “the day after.”

As things stand, the operational end state looks like significant Hamas infrastructure is destroyed, its fighting capability severely degraded, and the border secured, with the IDF retaining the capability to strike into Gaza at will.

All of this has occurred while shifting hundreds of thousands of civilians out of harm’s way and minimizing innocent casualties (Hamas’ human shield tactics aside).

As John Spencer, chair of urban warfare studies at the Modern War Institute at West Point, has repeatedly pointed out, the efforts the IDF has made to protect civilians is unprecedented in modern urban warfare.

Both the tactical and strategic accomplishments of the IDF campaign in Gaza are entirely real.

The operational design that allowed for these accomplishments does, of course, come with disadvantages.

First, the destruction of civil infrastructure will require a massive reconstruction effort.

While innocent civilian deaths are real and tragic, the almost 1-to-1 combatant-to-civilian death ratio remains very low compared to other conflicts.

Second, the Egyptians have been very twitchy about Israeli control of the southern border.

However, we now know why.

Since the start of the Rafah operation, the IDF has uncovered some 50 tunnels that run from Gaza into Egypt, suggesting a high and ongoing degree of complicity between the Hamas leadership and the military and political leadership in Cairo.

Militarily, the IDF is hamstrung by international pressure to slow operations, and uncertainty about what comes next in Gaza — a choice that may at least partially lie outside of Israel’s control.

For our part, Western critics need to eat humble pie and accept that, on the evidence of the last 20 years, our tactics are not to be recommended. What we are seeing in Gaza is not a failure.

It’s a quite brilliant IDF operational design, within the bounds of what is realistically possible.

No comments:

Post a Comment