|

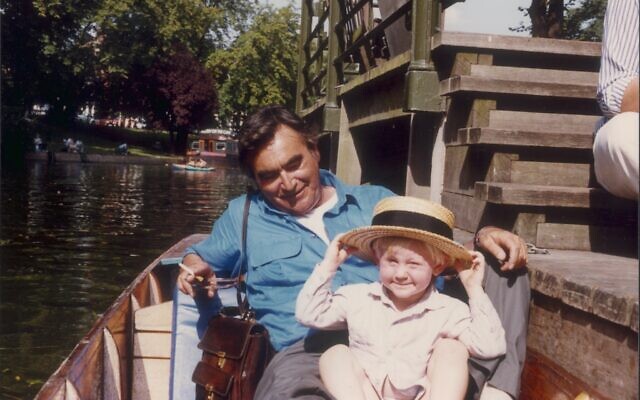

| Rudolf Vrba with daughters Zuza (left) and Helena (center) |

They didn’t know it, but it was the eve of the Passover seder. At 2:00 p.m. on April 7, 1944, 19-year-old Rudolf Vrba and 25-year-old Fred Wetzler began their epic and daring bid to bring the news of the horrors of Auschwitz to their fellow Jews and the wider world.

That bid began in a dark, cramped hole under a woodpile in the death camp. It ended with a report describing the Nazi machinery of slaughter which landed on desks in Allied capitals and, through a series of diplomatic maneuvers, helped to save the lives of up to 200,000 Jews in Budapest.

But, for more than seven decades, the story of Vrba and Wetzler’s astonishing escape — the first successful effort by Jewish prisoners to break out of Auschwitz — and their mission to sound the alarm and strip away the layers of deception under which the Final Solution was perpetrated has itself remained somewhat hidden. The recognition they rightly deserve has consequently been denied.

In his newly published book “The Escape Artist,” British writer and journalist Jonathan Freedland seeks to correct this historical injustice, painstakingly but grippingly reconstructing Vrba’s incredible life.

Freedland, a columnist for The Guardian newspaper and host of a popular BBC radio history program, tells The Times of Israel that his aim is to ensure that Vrba has, at last, “a place in the pantheon of heroes of the Holocaust.”

And, says Freedland, this is not simply a story about the past. Vrba’s belief about the potential power of shining a light onto Auschwitz’s dark secrets holds salutary lessons for our “post-truth age.”

Try, try again

Walter Rosenberg — the name Vrba was given to him as a cover after his escape from Auschwitz — was born in western Slovakia in 1924. A precocious child with a gift for languages and mathematics, he was forced out of school at 14 when Slovakia’s puppet regime, established following Hitler’s 1939 dismemberment of Czechoslovakia, introduced a series of antisemitic regulations.

When, in February 1942, Vrba was ordered to report for “resettlement,” his immediate thought was to escape to England to join the Czechoslovak army in exile. While he didn’t succeed, the teenager managed to make it to Budapest where he made contact with the underground. Eventually, after being roughed up by Hungarian troops, he ended up back in the hands of the Slovaks who sent him to the Nováky detention camp.

Nonetheless, Vrba’s determination to escape had in no way diminished. Indeed, he managed to slip out of Nováky with Josef Knapp, a young man from his birthplace. His subsequent betrayal by Knapp, which led to Vrba being returned to the camp, taught the 17-year-old an important lesson that helped him to survive what lay ahead: trust nobody.

When he was transported to Auschwitz in June 1942, Vrba soon realized that thoughts of escape had to be subordinated to the demands of simply staying alive. If distrust was one factor in Vrba’s survival, luck was another. Sent to IG Farben’s brutal Buna factory, he was recruited by a French civilian to do less onerous work. He was later transferred from the notorious gravel pits to a job painting skis for troops on the Eastern Front. And, after being selected for execution during an August 1942 typhus outbreak in which 746 men were murdered, he was saved by a kapo.

Perhaps Vrba’s greatest stroke of luck, however, was being sent to work in “Kanada,” a unit that sorted through the belongings of new arrivals at Auschwitz. The work included ferrying bags and rummaging through valuables, including squeezing tubes of toothpaste potentially containing diamonds or cash that had been stashed away. Crucially, however, the prisoners were also able to surreptitiously steal food that newly arrived prisoners had brought with them to the camp. The newcomers were, by this point, likely already dead.

Vrba’s time in Kanada slowly led him to a shocking realization: that Auschwitz was, as Freedland puts it, not simply a slave labor or concentration camp, but “a factory of death.” He also came to the sickening understanding that anything of value found in Kanada was shipped on trains back to Germany: The Nazis were attempting to turn a profit on their policy of mass murder.

Deception brought death

Vrba’s transfer to work on the “ramp” — where he spent 10 months helping to remove the luggage of new arrivals and clear out the cattle trucks — led him to grasp a final truth about the mechanics of this factory of death: that deception was crucial to its smooth functioning. Unaware of their fate, the deportees largely obeyed the Nazis’ instructions — inadvertently ensuring the order the SS required to commit industrial-scale murder. If the wheels of the killing machine were to be slowed, Vrba believed, this veil of secrecy had to be lifted and Jews needed to be forewarned of their imminent fate.

His close-up knowledge about the experience of the “family camp” — where, in another act of Nazi deceit, groups of Czech Jews were kept in relatively good conditions should the Red Cross choose to visit — led Vrba to revise his belief about the importance of information. The Czech Jews had been warned by the underground that they were to be murdered after six months. But, still, they did nothing to resist.

Knowledge, Vrba came to realize, had to be accompanied by the possibility of being able to escape the Nazi butchers. This may have been a near-impossibility in Auschwitz itself, but the door was still ajar for those Jews who had not yet boarded the trains. They had to be alerted.

For Vrba, escape thus became a mission that was about much more than his own survival. He sought nothing less than to shatter the wall of lies that the Nazis had constructed — a wall that surrounded their victims at every stage of their journey to the gas chambers.

Despite his youth, Vrba was well equipped to carry out this mission. Alongside his resilience, he was gifted with strong numerical and scientific abilities and an uncanny ability to retain data. He also had what Freedland terms an “almost uniquely panoramic view” of Auschwitz. Aside from the factory, gravel pits, Kanada and the ramp (where he counted and memorized details of the arrival selections), he also volunteered to work in Birkenau and, through his links to the underground resistance, became a registrar in a quarantine sub-section of the camp. As a clerk, he now had the opportunity not only to wander more freely around Auschwitz — committing to memory its layout and workings — he also had access to the chief registrar’s records which contained highly detailed information about the transports.

Statistically, though, Vrba’s chances of escape weren’t good. No Jew had ever achieved this perilous feat. However, he was, as Freedland notes, young and, thanks to the nature of the clerical work he had been doing, much fitter and healthier than most inmates. In Kanada, he had also found a child’s atlas and memorized the route from Auschwitz to the Slovak border. He also had invaluable mentoring from a Russian prisoner, Dmitri Volkov, who had once escaped from Sachsenhausen. Among the advice Volkov imparted was a crucial piece of intelligence: machorka, a Soviet tobacco, soaked in petrol and dried, was the only available substance that could throw the camp’s tracker dogs off of a human scent.

For Vrba, the clock was also ticking. In January 1944, he discovered that a new railway line, which ran straight to the camp crematoria, was being constructed in preparation for the arrival of Hungary’s roughly million-strong Jewish population. Hungarian Jews had hitherto been partially protected from the worst of the Final Solution. But that all changed when Hitler occupied the country in early 1944, snuffing out the last vestiges of Hungarian independence and forcing the country’s opportunistic leader, Admiral Miklós Horthy, to appoint a Nazi sympathizer as prime minister.

A desperate bid for freedom

Less than three weeks later, Vrba launched his bid for freedom. Accompanying him was Wetzler, a young man from his hometown with whom he had become friendly in the camp. The pair were well acquainted with the drill when a prisoner was found to have escaped: For 72 hours, the camp went onto high alert and a thorough search was conducted. But, after that point, the Nazis returned the outer camp — where prisoners labored by day before being herded back into the main came overnight — to its less stringent nighttime security arrangements. The plan was thus to hide in a makeshift bunker under the woodpile in the outer camp, then slip out under cover of darkness once the search was called off.

For three days and three nights, Vrba and Wetzler lay side-by-side in the dugout. Luck was once again on Vrba’s side. While the machorka had stopped the search dogs from giving them away, two guards had spotted the woodpile and begun to pull away the planks. But, when Vrba and his companion were just seconds away from discovery, the SS men were distracted by a commotion elsewhere and disappeared, never to return. In a further stroke of luck, as the three days came to an end, Vrba and Wetzler realized that the wooden planks concealing them were much heavier and more difficult to move than they had anticipated. If the SS guards hadn’t removed the first few layers of planks, the two men would have been trapped in the pit.

Vrba’s luck continued as the men began the 50-mile (80-kilometer) trek south, following the course of the Sola river, towards Slovakia. Despite taking the precaution of walking only after dark, they had plenty of narrow escapes: they accidentally stumbled upon a Hitler Youth camp; got lost perilously close to a subcamp at Jawiszowice; and awoke to find themselves, not as they’d believed, in a secluded wooded grove but a public park where SS men and their families were enjoying the Easter holiday weekend. They were even pursued and shot at by a patrol of German soldiers.

The gambles they took — necessary, though reckless — also paid off. A Polish peasant woman, believing them to be escaped Russian POWs, provided them with shelter when they struggled to find somewhere to hide out one day. Luckier still, 10 days into their trek, another Polish woman allowed them to stay in her goat hut, provided them with food, and introduced them to a man who guided the pair through the mountains to the border with Slovakia.

Making contact, saving lives

But getting to the relative safety of his homeland had never been Vrba’s sole goal. As soon as they crossed the border, Wetzler made contact with Slovakia’s Jewish council, the only communal organization the regime still allowed to function. The men were then subjected to a grueling 48-hour interview and cross-examination, both to establish their credibility and to record their story.

From their interviews, Oskar Krasnansky, one of the council’s most senior members, compiled a 32-page, single-spaced report, complete with professional drawings based on Vrba and Wetzler’s testimonies. The document was, Freedland writes, “bald and spare, free of rhetorical fire. It gave the floor to facts rather than passion.”

Still, the report methodically detailed the horrors of Auschwitz and, crucially, the fictions deployed by the Nazis from the moment the cattle truck doors were slammed on departure to that at which the gas chamber doors were locked.

Thanks to Vrba’s extraordinary memory, the report provided details of individual transports and a country-by-country breakdown of the estimated death toll during his time in the camp.

But, over Vrba’s strong objections, the report contained no warning to Hungary’s Jews that the camp was being readied for their destruction. Krasnansky was insistent: the document was to record only what had happened, not provide forecasts about the future.

Nevertheless, when two more Jews successfully escaped seven weeks later, Krasnansky added a seven-page addendum to the report which contained their account of the murder of Hungarian Jews when transports began to arrive from the now German-occupied country in May 1944.

Vrba was understandably frustrated that the warning he had been so desperate to sound had clearly not reached the latest victims of the Final Solution in time. But this wasn’t the full story. Within hours of the report’s completion, Krasnansky had personally handed the document to Rezso Kasztner, the de facto leader of Hungarian Jewry.

Meanwhile, having got their hands on a copy of the report, the anti-Nazi resistance in the country lobbied the most senior Protestant and Catholic bishops in Budapest to intercede with the government on the Jews’ behalf; the former acted immediately, the latter stalled and said it was a matter for the Pope.

Thanks to the energetic efforts of a Swiss-based British journalist who turned the report’s somewhat dry language into attention-grabbing press releases, Vrba’s revelations began to filter out in the press, including the New York Times, and on the BBC’s foreign services. Vrba himself was invited to brief a papal envoy who was visiting Slovakia.

Pressuring a regime to act

Horthy’s regime had a long history of antisemitism, but the Jews had a sympathizer close to the center of power: the regent’s daughter-in-law. Furnished with a copy of the report by the Hungarian opposition, Countess Ilona Edelsheim Gyulai passed it to Horthy himself. The regent declared himself appalled by what he read. He also soon came under external pressure — from the Pope, the United States and the Swedish monarch — to stop the deportations.

While the Vatican spoke in code and attempted to appeal to Horthy’s better angels, the Roosevelt administration bluntly warned that “all those responsible for carrying out [these] kind of injustices will be dealt with.” Painfully slowly, Horthy — who, as Freedland notes, was primarily motivated by personal self-interest — began to assert his tattered authority, ordering the deportations to stop and frustrating Adolf Eichmann’s impending plan to ship Budapest’s 200,000 Jews to Auschwitz.

For over 400,000 Jews who lived in rural Hungary it was, of course, too late. And, when the Nazis finally ousted Horthy in the autumn, the Arrow Cross launched a reign of terror in which thousands of the capital’s Jews were murdered. But Vrba had won enough time to ensure that, when the war ended, over 200,000 Hungarian Jews are believed to have survived.

But the feeling that more could — and should — have been done would haunt Vrba for the rest of his life. He would, for instance, never forgive the fact that, as part of Kasztner’s controversial deal with the Germans which secured exit permits for around 1,700 Hungarian Jews, Kasztner agreed to keep silent about what he and the small leadership group surrounding him had learned from Vrba’s report. Kasztner thus gave Eichmann and the SS, writes Freedland, “the only thing they deemed indispensable for their work… order and quiet.”

Inaction by the Allies

Then there is the question of how the Allies responded to the report. The report reached London speedily and was read by Churchill, who immediately agreed to a request, passed on by Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, that the railway line between Budapest and Auschwitz should be bombed. But, once passed down the chain of command, military objections were raised as to the feasibility of such a raid.

The US, too, opted for inaction. “Bureaucratic buck-passing and paper shuffling,” as Freedland describes it, characterized the response of US diplomats in Switzerland when they received the report. Urgent appeals for bombing, passed through Jewish community contacts in the US, met a wall of resistance. Roosevelt himself decided that the US could end up “accused of participating in this horrible business” were its bombs to end up killing Jews.

Reactions to the report in London and Washington also revealed that, despite the horrors it contained, old prejudices remained unshaken. The US Army magazine, Yank, for instance, declined to use material from it in a feature on Nazi war crimes, requesting instead “a less Jewish account.” Meanwhile, in the UK Foreign Office, civil servants bemoaned the “usual Jewish exaggeration” and the amount of time expended on “these wailing Jews.”

But, alongside these responses, there was also a swirl of disbelief surrounding the report’s revelations: one which affected not only the Allies but even some Jews themselves. It was perhaps best captured by the words of the French-Jewish philosopher Raymond Aron: “I knew, but I didn’t believe it. And because I didn’t believe it, I didn’t know.”

“I think this goes to something very profound about human nature and our limited ability to hear terrible news,” says Freedland. “We can have the information without it ever becoming something we fully, truly believe.”

Facts, he says, have to be combined with belief before they become knowledge, which is itself the spur to action. For all his insights into how the Nazis were using deception to perpetrate their terrible crimes, the teenage Vrba hadn’t reckoned on such sentiments.

An ‘ultra witness’ bearing uncomfortable testimony

After the war, Vrba returned to his native Czechoslovakia, later living in Israel and Britain before finally settling in Canada. He married twice — the author interviewed first and second wives Gerta and Robin for this book — and had two daughters, Helena and Zuza. Vrba also had a successful academic career as a biochemist.

He also became what Freedland terms an “ultra-witness”: writing his own memoirs; giving expert testimony in multiple cases involving war criminals and Holocaust deniers; and sharing his perhaps unparalleled insights into the working of Auschwitz with the foremost chroniclers of the Shoah, including the historian Martin Gilbert and documentary-maker Claude Lanzmann.

Vrba’s story, however, never obtained the wider recognition or status afforded to other rescuers, like Oskar Schindler, or fellow survivors such as Elie Wiesel or Primo Levi.

“I think it’s because he was an awkward, uncomfortable witness who spoke awkward, uncomfortable truths,” says Freedland. “He pointed an accusing finger, partly at Whitehall and Washington… [but], much more sensitively, at a limited number of individuals in the Jewish leadership, specifically in Budapest. That was not a story many people wanted to hear in Rudolf Vrba’s lifetime.”

But, as Freedland says, reactions to Vrba’s story reflect a wider issue with how Holocaust survivors have often been treated.

“I think we — the media, educators, and others — have put, and continue to put, a very unfair pressure on Holocaust survivors to serve up a sort of comforting, healing wisdom and to make us feel better for having spoken to them,” he says.

This pressure, he continues, denies survivors the opportunity to express “a range of responses to the gravest possible trauma, including anger.” Vrba’s response, of course, was anger — an anger which few readers of the book will conclude was unjustified.

Freedland believes that Vrba, who he terms a “hero for our times,” should not simply be judged by his past heroism but also by his current relevance.

In a post-truth age — where so many lies proliferate through social media, propaganda and active disinformation — the story of this teenage boy from the 1940s serves as a reminder “that the difference between truth and lies can be the difference between life and death,” he says. “Rudolf Vrba could not be a more contemporary figure and, in some ways, an urgently inspiring one.”

6 comments:

Vrba's escape is very well known as were his attempts to alert the world to what the Nazis were doing. There is abundant documentation as well as his own book I Escaped Auschwitz

This is the first time to my knowledge that din writes about kasztner in a negative way. He's always hailed as a Zionist hero

The legendary Rabbi Michoel Ber Weissmandl. Who was instrumental in alerting the world to the Nazi atrocities, got all his information from Vrba.

Rabbi Weismandl was one of the first ones to interview Vrba when he arrived to Slovakia

1:46

I'm not the one who wrote this about Kastner. I believe he was a hero though not a tzaddik.

In which regard was he a hero? By saving 1700 instead of?

12:23

See

מסכת סנהדרין פרק ד' משנה ה'

כל המקיים נפש אחת, מעלים עליו כאילו קיים עולם מלא

Post a Comment