On a Friday night in February 2015, the legendary British Jewish neurologist and writer Oliver Sacks gathered his inner circle in his New York City apartment. For much of his life, Sacks had penned poignant books about his disabled patients, sharing insights about their lives. On this night, however, Sacks gave his audience a heartfelt message about his own life: He had received a terminal cancer diagnosis.

Over the next six months, Sacks gave what one of his friends, the author Lawrence Weschler, called “a master class in how to die.” He continued to write thoughtful prose, this time meditating on mortality, in the company of family, friends and his partner Bill Hayes.

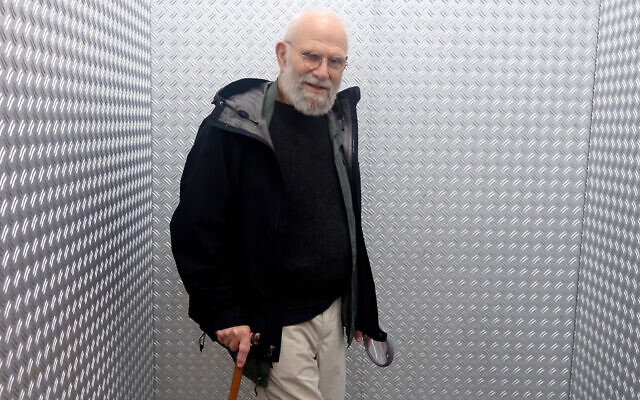

Sitting for filming sessions with award-winning documentarian Ric Burns, Sacks reflected on an extraordinary, sometimes tumultuous life — running away from an Orthodox upbringing, wrestling with his homosexuality, facing rejection by the scientific community for much of his career and finally winning admiration from academia and the public. The year he died, 70 percent of neurology majors at Columbia University Medical School credited Sacks, at least in part, as the inspiration for their choice of study.

Five years later, filmmaker Burns is ready to release his documentary about Sacks to the public. “Oliver Sacks: His Own Life” debuts September 23, through New York’s Film Forum and the Kino Marquee virtual cinema platform. Over the previous year, it was screened at Telluride and the New York Film Festival. Although the general release was delayed six months by COVID-19, Burns is excited that the public now has a chance to see it.

The winner of two Emmy Awards and a Peabody Award, Burns is part of a celebrated duo of American documentarians. He and his brother, Ken Burns, worked together on the 1990 epic “The Civil War” before going on to make separate ventures. Ric Burns has directed a similarly epic series about the history of New York City, and is working on the latest installment, which will cover the period from 9/11 to the COVID-19 era.

In a phone interview with The Times of Israel on August 30 — the fifth anniversary of Sacks’s death — Ric Burns described the unexpected genesis of his latest-released project.

Early in January 2015, Sacks had just finished what Burns described as “a not-yet-published, remarkably candid autobiography.” Around that time, the filmmaker got a call from Sacks’s longtime editor and chief of staff, Kate Edgar.

“Oliver is dying,” he remembered her saying. “Would you come in and film him?”

“He got a mortal diagnosis and very much wanted to share the time he had,” Burns said. “He was told he would die in six months. Indeed, he died in six months. He wanted to think, reflect, explain himself, not only in print, but also on film.”

“It was kind of a very different way of doing a film,” Burns said, adding that usually, “someone brings the idea to you, you talk about it and reflect how to go on — writing, interviewing people, fundraising.”

This film, he said, was a “yes” project from the start, and time was of the essence.

Burns embarked upon marathon filming sessions at Sacks’s apartment on Horatio Street in Greenwich Village. Shooting for a total of 80 hours, sometimes using multiple cameras, he filmed Sacks and the rotating circle of loved ones who checked in on him. Prominent journalists and writers dropped in, including surgeon-writer Atul Gawande, and Temple Grandin, an advocate for animal rights and autism awareness. Also interviewed for the film was the theater and opera director Sir Jonathan Miller, who was a friend of Sacks’s since childhood.

“[Sacks] was always sort of surrounded by, in a sense, the family he created for himself during his lifetime,” Burns reflected. “That itself was really quite unique.”

Sacks’s background was also unique. Burns describes him as an atheist homosexual English Jew, and the film sensitively addresses each of these aspects of his life. Notably, he was the uncle of former British chief rabbi Jonathan Sacks, who was criticized in 2013 for his opposition to civil marriage for gay couples in the UK.

A remarkable life unfolds

Oliver Sacks was born in 1933 to accomplished Orthodox parents Samuel Sacks, a general practitioner, and Muriel (Landau) Sacks, who was among the earliest female surgeons in the UK. Sacks was their fourth child. He was a distant relative of Israeli statesman Abba Eban and Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert John Aumann.

Sacks’s childhood was interrupted not only by the Blitz, but also by his brother Michael Sacks’s struggle with schizophrenia. A few years later, when Oliver Sacks turned 18, he came out as gay to his father, and soon his mother learned as well. According to the film, she called him an abomination and wished he never had been born.

“In a sense, from that moment on, he was on the run,” Burns said. “He was escaping his mom, family, sexuality, himself,” with Sacks “running from madness, trying to hide it, soothe it, exacerbate it.”

After receiving his medical degree at Oxford, Sacks left for the United States, finding an uneasy refuge in San Francisco, where the film shows him setting a weightlifting record, having an unsuccessful relationship with a man, taking recreational drugs and going for risky motorcycle rides — all while undertaking a medical residency at UCLA.

He got a new start when he relocated across the country to Beth Abraham Hospital in the Bronx. There, he treated patients left catatonic by a sleeping sickness epidemic from the 1920s. He took the unorthodox step of prescribing a drug called L-dopa. Initial results seemed promising as patients began to walk and talk, yet they had to contend with side effects of the drug and some reverted to their previous condition, according to an article on the NIH website.

Sacks wrote about these experiences in his book “Awakenings,” which he penned with his mother’s input in the family home on Mapesbury Road in London after mending ties with her.

The film shows Sacks continuing to write about his disabled patients in books and articles. After “Awakenings,” for instance, there was the anthology “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat.” The media proved receptive to Sacks’s contributions.

“I’d read many of his books, I knew him the way most people did,” Burns said. In addition to Sacks’s books, he frequently wrote contributions to The New York Review of Books and The London Review of Books.

Making disability palatable

Burns characterized Sacks’s writings as a bridge between disabled individuals and the wider world. He embodied a trove of data that colleagues initially misjudged as meaningless.

“The data he collected and summarized in his stories was uniquely qualified data — a narrative of interesting, subjective experience,” Burns said. “To know what [his patients are] like, not what it looks like on an MRI, to be a person with myopathy, autism, a neurological condition, whatever it might be.”

The film examines Sacks’s detractors, including those who accused him of sensationalizing his patients. Yet, Burns said, by the 1980s and 1990s, things began to change. The 1990 Robin Williams film adaptation of “Awakenings” brought Sacks large-scale fame, while his ideas won acceptance from respected colleagues such as Francis Crick, who won the Nobel Prize for the co-discovery of DNA.

“[Sacks’ work] suddenly seemed relevant,” Burns said. “For most of Oliver’s life, it had been meaningless, unqualified, not data at all… not measurable. But Oliver did not measure in numbers, but in words.”

The hidden decades

While reading Sacks’s books and articles, Burns noted that something was missing.

“From the ’80s on, I did not know anything about his life,” Burns said. “He was guarded until the very end. Openness was something he arrived at only at the very end.”

Sacks had an earlier bout with melanoma in 2005. When it returned a decade later, the diagnosis was terminal.

Burns kept the camera on when Sacks announced the diagnosis to his inner circle.

“Here is a person coming to the end of his life, facing the inevitable, with the people around him who mean the most,” Burns said. “His boyfriend Billy, his longstanding writing partner Kate, his sister-in-law… He was intensely aware of who we were. And, you know, he wanted to talk about what matters in life.”

Weeks before Sacks’s death, he penned an op-ed for The New York Times entitled “Sabbath,” in which he reflected upon his Jewish background, including family Shabbats, living on a kibbutz as a young man and returning to Israel with his partner decades later for the 100th birthday of a relative. He described an unexpectedly welcoming reception for both himself and Hayes, and mused on what might have happened had he stayed observant.

“He lost his faith early on,” Burns said. “He was not going to be himself an Orthodox Jew. But the experience of it — Shabbat, the seder — and also the reverence for what was ultimately a world [where] mysteries could be possible, was never fully conquered and he carried within himself a profound sentiment, sort of a Judaism without the religious belief in a supreme being, but a deep sense of the holiness of existence.”

Calling Sacks’s Judaism “central and shaping,” he added that it was “intrinsically, of course, complex and a journey.”

“He was not a saint, but led a life in which he was always moving toward what he understood as the light,” Burns said. “[This] meant understanding and connection — how do I understand myself, how do I understand another human being, how do I make connection, how do I share that connection, how can I be honest?”

1 comment:

Oh come on, old Shmuel Kaminetzky is a much bigger mumche on how to die with polio, measles, coronavirus, etc

https://forward.com/news/455103/schools-are-not-reporting-covid-cases-among-students-asking-teachers-not/

Some Haredi yeshivas in Brooklyn are asking teachers not to get tested for COVID-19, and also not sharing information about students who test positive, to try to avoid school closures, said 3 sources with direct knowledge of specific schools said in interviews.

The news comes amid an uptick in COVID in 6 Queens-Brooklyn neighborhoods which include the “Ocean Parkway Cluster” of Borough Park, Midwood & Bensonhurst, according to a Department of Health statement.

At Bais Yaakov of Boro Park, administrators called teachers individually and asked them to do the school a “favor” & not test — “even if you have fever,” wrote one teacher in a text shared with the Forward. The school, with 2,000 students, told faculty to only seek testing if the school asks for it.

That school is one of many who have adopted this & similar strategies in order to remain open, said parents of students in Haredi Boro Park, a Brooklyn neighborhood home to several Orthodox communities, including Satmar, Bobov & Belz.

“This is one of the more open-minded schools in Boro Park, so I wouldn’t put it past other schools doing the same thing,” said one Boro Park resident, who spoke on condition of anonymity & who has direct knowledge of similar policies in this school & others. “They want to keep schools open at whatever cost.”

Other schools in the Satmar & Bobov communities have similar policies, said a Boro Park parent, who has children in several schools: “Schools tell students don’t tell anyone there was a student with COVID in school.”

The parent noted that there are outliers; Bais Brocho, affiliated with Karlin Stolin, tried to keep its classes socially distant when they had their first case a few weeks ago. The Stoliner Rebbe is one of the few Hasidic rebbes who is encouraging social distancing.

New York’s Haredi neighborhoods had been hit hard by the virus earlier this spring, with some estimating at least 700 deaths in the early weeks.

Post a Comment