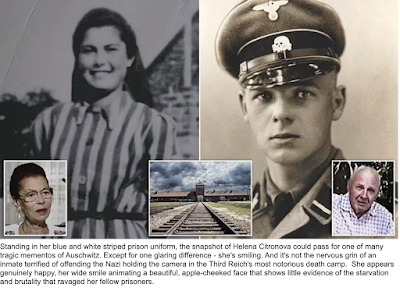

Standing in her blue and white striped prison uniform, the snapshot of Helena Citronova could pass for one of many tragic mementos of Auschwitz. Except for one glaring difference — she's smiling.

And it's not the nervous grin of an inmate terrified of offending the Nazi holding the camera in the Third Reich's most notorious death camp.

She appears genuinely happy, her wide smile animating a beautiful, apple-cheeked face that shows little evidence of the starvation and brutality that ravaged her fellow prisoners.

In fact that's because Helena wasn't performing for the camera as the man holding it, SS Unterscharfuhrer Franz Wunsch, was her lover.

'Yes, she was the love of his life,' says the Nazi's daughter Magda nearly 80 years later.

He treasured that photo, I know. He would take reproductions. He copied the picture and I know he even took the head off and put it on different clothes, on a different background.'

It's not surprising Wunsch might want to forget where and when the photo was taken. His romance with Helena is surely one of the most astonishing and unlikely stories to emerge from World War II.

And it is the focus of a documentary by Israeli filmmaker Maya Sarfaty called Love It Was Not, which offers an extraordinary insight into a tale of forbidden love.

It features interviews with more than a dozen of Helena's fellow inmates, the surviving families of both Wunsch and Helena and never-before-seen home video of the SS man matter-of-factly explaining the relationship.

Helena, daughter of the town cantor — the man who led the chanting and singing at the synagogue — in the Slovakian town of Humenne, had hoped she was destined for a career on the stage.

Instead, in March 1942 at the age of 19, she was put on a train with 1,000 other Jewish girls and deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

In her first days at the extermination camp, she was assigned to a kommando, or work detail, to demolish partially-destroyed buildings on the site.

Guards banned them from fleeing falling masonry and, as Helena recalled in an interview before her death in 2005: 'We weren't allowed to run so, when the wall came down, the first girls were crushed and died on the spot'.

This carnage went on for weeks and, in their desperation to survive, the girls would push each other to the front. As Helena observed: 'Very quickly, we had turned into animals.'

She realised that if she was to stay alive she would have to get a transfer to a less arduous kommando and a friend told her about 'Canada', a huge warehouse on Auschwitz's second site at nearby Birkenau, where the belongings of Jews and other condemned people brought to the camp were processed before they were sent to the neighbouring gas chambers.

Inmates who worked there would find food or warm underclothes in the suitcases, so jobs at Canada were highly prized. Helena succeeded in appropriating the uniform of a Canada worker but, after her deception was rumbled by a guard, she faced being sent to the penal kommando — which was an almost certain death sentence.

Then fate intervened. Word went out that the guards were looking for a singer to perform at the birthday party of Canada's commander. Helena had a fine singing voice and, as the other girls pointed out, if she made a good impression she might get a permanent job at Canada and escape the rigours of the penal kommando.

'I thought, 'I'm better off singing than dying',' she said.

Helena's repertoire of German songs was limited and she plumped for Love It Was Not, a poignant ballad about a loveless affair that wasn't exactly appropriate for the occasion. There were tears running down her face as she sang it, but it did the trick for the birthday boy Wunsch, a 20-year-old Austrian, who came up to her afterwards and asked her to sing it again just for him.

Helena was shocked. 'Suddenly I hear the voice of a human being, not the roar of animals,' she later recalled. 'I hear the word 'please'. I look up with tears in my eyes and I see a uniform and I think, 'God where are the eyes of a murderer? These are the eyes of a human being'.'

And Wunsch was looking at a woman still in her teens with big dark eyes, who had a freshness about her that would have stood out amid the horror of the death camp. 'She was like a peach. You just wanted to pinch her cheek,' recalled fellow prisoner Roma Ben Atar Notkovich.

Unsurprisingly, Helena stayed in Canada. Initially, she said she couldn't bear to look at Wunsch, having heard rumours that he'd killed a prisoner for dealing in contraband. 'I hated him at first,' she said. 'He was evil like all the SS. But as time passed...'

The Nazi surreptitiously slipped her food, even biscuits, then notes with messages such as, 'Don't worry, I'll get you out of here'.

Their growing attraction to each other didn't escape the notice of other Canada inmates.

He would only talk to her and she would sing to him. On one occasion he brought her a sheet and pillow to put over the flea-infested straw mattress in her freezing dormitory. Often he would stand by and watch her while she slept. 'He loved me to the point of madness,' said Helena.

Wunsch kept a diary and recorded how, in December 1942, Helena caught typhoid, a disease which, in Auschwitz, invariably proved fatal. He set up a bed on top of shelves in the Canada warehouse where he could care for her, giving her most of his SS rations and even the 'care packages' he was getting from his mother.

The relationship was an open secret both among inmates and fellow guards, and Helena lived in constant fear that someone would inform on them to the camp's senior commanders.

Both could have expected a death sentence because a guard having sexual relations with an untermensch, an inferior person, constituted a serious breach of SS racial purity rules.

While inmates close to Helena also benefited from Wunsch's food donations and kid-glove treatment, others were either furious at what they saw as her treachery, or envious as she avoided the gnawing hunger the rest of them felt.

Another former inmate, Bat-Sheva Dagan, said: 'Everyone was jealous, deeply, of the very fact that she had that chance, and we would go like sheep to the slaughter.'

'These women were bitter and rightfully so,' Helena acknowledged. She said some of them would whisper abuse or even, when they got the chance, beat her up. The relationship between Wunsch and Helena lasted for more than two years and she admitted that she felt deeply conflicted about it at times. In her defence, she claimed: 'I saved many people thanks to him.'

Women would come to her seeking help and she would pass Wunsch notes which simply gave the prisoner's number and the word 'Help'. He would read the note and tell her, 'For you, anything.'

Some of her fellow prisoners confirm this was true, pointing out that Wunsch overlooked infractions that other guards would have beaten them to death for. One recalled how she had once been stricken by typhus and a 40 degree fever, and was sprawled out among the clothes she was supposed to sort. She would 'never have survived' if Wunsch hadn't pretended not to see her.

But was it just to impress Helena? Another survivor testified how Wunsch was a 'real sadist... like a completely different person' when it came to his treatment of the male prisoners, who he would beat savagely when they came to collect clothes packages.

On several occasions, said witnesses, Helena would see him deliver these beatings and grab his hand to make him stop. In October 1943, said Helena, 'someone had reported that we were in love' and she was thrown in a prison cell where there was barely enough room to curl up on the floor. For five days she was interrogated about Wunsch and regularly put up against a wall and told she was about to be shot.

But she stuck to her story, pleading innocence and, amazingly, was not executed. Wunsch did the same during five days of questioning but, when he was hauled before an SS court and gave the Nazi salute, the judge winked at him before releasing him.

However, this brush with death failed to break up the young lovers, who continued their relationship, albeit more discreetly. Fellow survivors believe their affair was never consummated, pointing out that inmates slept packed together in triple bunks.

Sex 'would have been impossible,' said Bat-Sheva Dagan.

But there could have been other opportunities, as Wunsch later admitted that his immediate superiors turned a blind eye to the affair, one confiding: 'Such a beautiful girl. I can see why.'

While he was besotted with her from the first, Helena admitted her feelings deepened for him as she saw him repeatedly risk his life for her. 'Eventually, as time went by, I really did love him,' she said.

One incident in particular transformed her feelings — he saved her beloved sister Roza's life. Many of her family had already been killed at Auschwitz when, one day, she heard that Roza had arrived at the camp with her newborn son and six-year-old daughter.

Ignoring a curfew, Helena ran to the crematorium where, under the command of Josef Mengele — the notorious Auschwitz doctor dubbed the 'Angel of Death' — the SS had already put the trio in the queue for the gas chambers.

After pleading unsuccessfully for their release, Helena told the guards she wanted to die with them. The SS men were about to grant her wish when Wunsch, alerted by an inmate, arrived. Making a great show of beating Helena savagely for breaking curfew, he whispered, 'Quick! What's your sister's name?' before assuring Mengele that Roza would be a useful worker.

Roza was in the changing room taking off her clothes for the 'shower' they had been promised when she was plucked to safety.

Tragically, there was to be no escape for her children. Apart from the twins on whom Mengele performed his experiments, the Nazis had no interest in keeping children alive and the two little ones continued into the gas chambers.

By January 1945, the Russians were so close to Auschwitz that inmates could hear their guns. The SS guards were sent to fight at the front and the inmates were evacuated. Wunsch related in his diary how he went to make his final farewell to his 'proud, race- conscious Jewess' in her otherwise empty barracks.

'I've loved you very much.' he told her, writing: 'Now she has tears in her eyes. 'I beg you, Franz, don't forget me'. These are her last words. She embraces me one last time. We kiss long and intimately.' 'I had feelings for him then, that's for sure,' Helena acknowledged years later.

Both of them survived the war — Wunsch's last act was to give the sisters furry boots for the frozen, forced 'death march' away from Auschwitz — and returned to their home towns.

He made frantic efforts to locate her following the end of hostilities, writing endless letters in which he said he still loved her and hoped they could be reunited.

'Then we will be together and keep the many promises we made each other,' he gushed, adding regretfully: 'How completely different it would have been if we had won the war.'

But within a year of liberation, she had married a local Zionist activist. One of Helena's relatives eventually wrote back requesting Wunsch stop, saying it was strictly forbidden to be in contact with 'Nazi criminals' and that the blood of the two little children he had allowed to be gassed 'will never be washed off your hands'.

Friends say Helena was frightened Wunsch might find her so they moved to Israel, judging that even he wouldn't dare go there.

But the trauma she suffered in Auschwitz never left her. Her three children told the documentary-makers that their mother was afflicted by violent rages in which she would smash up the furniture and once claimed their family was cursed.

There was to be one final extraordinary twist in the story of the star-crossed lovers. In 1972, Wunsch was put on trial in Austria for murdering and gassing Auschwitz inmates.

He was by then married, too, and his wife, Thea, wrote to her love rival pleading with her to give evidence in his defence.

Helena accepted she faced a terrible dilemma but, ignoring death threats from Israelis outraged she might help an SS killer, she attended the trial in Vienna.

'I had raised a family. I had fallen in love with my husband. But the past still haunted me.'

Observers at the trial noted that Thea Wunsch only dressed up and wore make-up on the day Helena testified. Helena never looked at Wunsch from the witness box as she told the court he 'was always very good to me' and other women inmates, but described how he would beat male prisoners.

She said he'd once asked her to bandage his hand after one beating but she refused, telling him she 'wouldn't bandage the hand that beats my brothers'. Wunsch wept during her testimony.

He claimed he'd been corrupted at Auschwitz but denied beating anyone to death or herding inmates into gas chambers and said he would have preferred to have been at the front.

He was acquitted — as most Austrian Nazis were — and Helena's friends say she never spoke about him again.

The same could not be said of Wunsch. In a home video made in 2003, he can be seen explaining to his family, without any embarrassment, his relationship with Helena in the death camp.

And his daughter Magda recalled how, when she was 16, her father told her that he had 'never in his life felt true love' like he had for the woman he'd left in 1945, which, she said, 'made me feel a little uncomfortable'. He then gave her a double locket containing photos of him and Helena. 'I thought that was a bit odd. It should have been my mother in there,' Magda told the filmmakers.

But then, what wasn't odd about the love affair between the SS guard and the Auschwitz inmate?

ADVERTISEMENT

1 comment:

Aren't goyim (gentiles) untermenschen, according to us? Then we complain when they turn the tables on us? For how much longer will we be this stupid?

Post a Comment