In 1948, FBI head J. Edgar Hoover was sharply focused on the Communist Party of the USA to root out Russian espionage — and with his attention concentrated there, missed the escape of a highly accomplished Soviet spy hiding in plain sight.

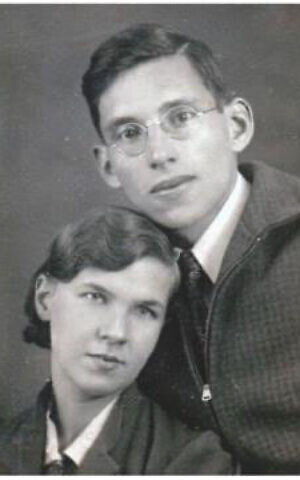

Born into a Jewish family that had immigrated from czarist Russia to the United States, George Koval habitually joined groups and clubs — a bowling league, bridge-playing circles, an honorary fraternity of electrical engineers. He also joined the US Army and conducted top-secret work at two locations of the Manhattan Project, which developed the atomic bombs that exploded over Japan in 1945.

In 1949, the year after Koval’s return to the USSR, the Soviets successfully and shockingly detonated their own atomic bomb.

Now, Koval’s life is the subject of a new book, “Sleeper Agent: The Atomic Spy in America Who Got Away,” by former Wall Street Journal reporter Ann Hagedorn.

“I just think there’s a lot to be learned by George Koval’s story,” Hagedorn told The Times of Israel in a phone interview.

“It transcends a typical spy story. Yes, this is a spy story — there are code names in it. It’s thrilling. There’s a handler — a fascinating handler — and surveillance. But it transcends that. It’s really about the psychology of a spy and also about what motivated him. It’s about the backlash of bigotry… He knew the tremendous cost of oppression.”

An un-American tale

Koval’s parents were part of a relatively obscure migration of Jews escaping antisemitism in Eastern Europe for the US in the early 20th century — the Galveston Project, named after the Texas port that became a southern alternative to Ellis Island.

After spending his first years in what was then a thriving Jewish community in Sioux City, Iowa, Koval and his family left an increasingly antisemitic America in another arguably obscure Jewish migration as the Soviets formed the Jewish Autonomous Region in the Russian Far East.

Koval’s father Abram Koval was a regional representative for the Association for the Colonization of Jews in Russia, or IKOR — a group that helped coordinate Jewish migration to the Autonomous Region and its administrative center in the town of Birobidzhan.

“These were new parts of history for me, the Galveston Movement and also IKOR and the Jewish Autonomous Region,” Hagedorn said. “It’s a fascinating part of Jewish history, I think.”

George Koval eventually went to Moscow, where he graduated from the prestigious Mendeleev Institute and showed a knack for science. Despite the increasing paranoia of Joseph Stalin, Koval remained a believer in communist ideals, but feared for the safety of his family, including his Russian wife, Lyudmila. The two factors of communist idealism and pragmatic protection of his family, Hagedorn says, motivated him to become a spy.

Returning to the US, Koval enrolled at Columbia University, which at that time was becoming a nexus for some of the top academics who would work on the Manhattan Project. Drafted into the US Army, he took advantage of a government program that recruited individuals with scientific and technical knowledge for the top-secret, multi-location attempt to invent an atomic bomb. Soon, Koval was driving a Jeep and working at top-secret locations in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Dayton, Ohio, penning papers about safety techniques while keeping his eyes open about nuclear fission and the use of radium and polonium to make the bomb.

“We’re talking about a period of time when George Koval was in the US as a Red Army military-trained spy with full US security clearance,” Hagedorn said.

According to Hagedorn, there were multiple reasons for Koval’s going undetected. There was a need for his scientific expertise, she said, and the Soviet Union was then a US ally. Koval’s background growing up in the Midwest also helped him blend in.

A spy you probably never heard of’

Koval came to Hagedorn’s attention in 2016, when she was working on a separate project about World War I and interviewing a 92-year-old man whose father was connected to the story. It turned out that she and her subject had both grown up in Dayton, and at the end of the interview, he mentioned that Dayton had been a Manhattan Project site.

“He said there was a Soviet spy living there during World War II you probably never heard of,” Hagedorn recalled. “I said, ‘Interesting. What was his name?’ He didn’t know the name or anything else at all, [so] I took a week off to see if I could find this guy’s name.”

She found his name and more in a 10-year-old New York Times article following Koval’s death in 2006.

“[It was] a very excellent story about a spy they believed was one of the most important spies of the 20th century, noting that Vladimir Putin had just given [him] a posthumous award,” she said. “It gave his name: George Koval.”

Hagedorn embarked on an ambitious project to learn more about Koval through research at places like the National Archives and the Center for Jewish History, examining sources from newspaper clippings to school yearbooks, tax records and ship manifests, as well as thousands of pages of FBI reports, some of them gained after filing Freedom of Information Act requests.

She found a later-in-life correspondence between Koval and a former colleague in the US, in which the former expressed no regrets for his espionage. Another document testified to his prowess as a spy.

When Koval returned to the USSR, he found an increasingly antisemitic climate, in which his American birth and Jewish identity might count against him. After Joseph Stalin’s death, some of the antisemitism abated and Koval pleaded for help from his past employer — the GRU, predecessor to the KGB — and its notorious head, Lavrentiy Beria. A letter soon found its way to his alma mater in Moscow, the Mendeleev Institute, instructing them to help him.

“The fact that Beria, and the fact that the GRU, answered his letter in 1953 after Stalin died is the living proof of their respect for him,” Hagedorn explained.

After all, she noted, “he blended in. He was all-American.”

An accent like apple pie

Born in Iowa, Koval spoke without a foreign accent and loved the American national pastime of baseball. Had any of his future employers at the Army or the Manhattan Project done any digging, they might have found evidence of early communist leanings as a teenager — participation in a communist youth gathering in Chicago, and an arrest while standing up for people impoverished by the Great Depression.

By the 1930s, the US was growing more antisemitic, as reflected by the Red Scare and the increasing presence of the Ku Klux Klan, including in Sioux City. The Koval family, which now numbered five — George, his two brothers and their parents — joined the Jewish community of Birobidzhan and found that life there was far from paradise. Yet the family stayed there, except for George, who wound up in Moscow.

After training as a scientist, Koval agreed to become a spy for the GRU.

“He was dedicated to science and dedicated to the communist ideal,” Hagedorn said. “To me, his top priority, I think, was loyalty to his family. Joining the Red Army military, becoming a Red Army military intelligence officer in 1939, he would be protecting his family… If he had been killed [in action], his family would have been taken care of.”

In the US, Koval took care of his family by staying under the radar for eight years. He lived in a Yiddish-friendly housing complex called the Sholem Aleichem Houses and remained incommunicado with other Soviet spies of the era except his handler — a fellow Jew named Benjamin Lassen (originally Lassow), a Bronx-based agent who operated out of his Manhattan business-office front.

When the US Army drafted Koval in 1943, it missed the fact that he was a graduate of the Mendeleev Institute, but noted that he had taken a course in chemistry at Columbia — exactly what the military needed for an elite group called the Army Specialized Training Program.

“It was a highly scientific group of gentlemen sent to different sites of the Manhattan Project working with scientists,” Hagedorn said. “Their specific scientific training helped the military.”

Koval worked as a health physicist — “a very new field,” Hagedorn said. “These were gentlemen studying safety procedures to protect workers from radiation contamination. They did all kinds of studies of radiation, creating instruments, measuring dust particles in the air.”

And, she said, health physicists like Koval had access to “all facilities” of the Manhattan Project: “It’s certainly what helped him as a Soviet spy.”

The project soon realized its goals. On August 6, 1945, the US detonated an atomic bomb over Hiroshima, Japan. Three days later, on August 9, it detonated another bomb over Nagasaki, leading to the end of WWII.

Within a year, Koval was growing nervous about anticommunist sentiment in the US, and began requesting that the USSR send him home. He also turned down a job offer from the US Army.

“I think his handler and others wanted him to take the job,” Hagedorn said. “He knew the security would be huge,” and that it would be very possible for the US government to dig up things from his past, such as the 1930 Communist Youth League conference he attended or his arrest a year later.

“He was smart,” Hagedorn said. “He knew all these possibilities could be discovered and he left in 1948 as soon as he could.”

It has been 15 years since Koval’s death, yet he remains enigmatic — including to the author.

“I would have loved to have interviewed him,” Hagedorn said. “What would be the first question I would ask him? ‘OK, why did you do it?’”

No comments:

Post a Comment