|

| Tuly Ziv and his son, Noam |

Some 60 years ago, on the night between May 31 and June 1, Pinchas Zacklikovsky returned to his home in Bnei Brak, entered his 10-year-old son Tuly's room, and told him quietly and calmly: "Tonight I cremated Eichmann."

Zacklikovsky, a professional oven-builder, who spent the war years in the Lodz Ghetto and Buchenwald Concentration Camp, didn't depart from his routine. "The next day dad went to work like nothing had happened," Tuly says. "They asked him 'how was it?' and he answered 'I turned on the oven, put the body in, and that was that. All I did was turn Eichmann into ashes.'"

In 1940, Nazi arch criminal Adolf Eichmann visited the Lodz Ghetto in order to monitor up close the operation to expel the Jews, as the preliminary step towards the implementation of the Final Solution. Someone who saw the senior Nazi officer from a distance was Pinchas Zacklikovsky, then a young man of 20.

Pinchas Zacklilkovsky was born in 1920 in Poland to a wealthy family of Gur Hasidim. He was raised alongside four brothers and sisters, and like every Jew in Europe was greatly shaken by the outbreak of World War II. At the beginning he escaped on his own, wandered throughout Poland in areas that were then controlled by the Soviet Union, in an attempt to escape from the clutches of the Nazis, but in the end, he decided to return to his family and be with them during those dreadful times.

From the Lodz Ghetto he was transferred to the Czestochowa Ghetto and in 1944 he was sent to Buchenwald Concentration Camp. "They beat his father to death right before his eyes," Tuly says. In an interview with the newspaper Yom HaShishi in 1990, Zacklilkowsky said that, after the American army liberated the Concentration Camp from the Nazis, he angrily set upon a German officer who had tortured him, and ripped out both of his eyes.

He made aliyah in 1946 on the Enzo Sereni ship, but was then expelled with the other "illegal" immigrants to Cyprus and was afterwards imprisoned in the Atlit Detention Camp. Afterwards he was recruited into the Etzel, and during the War of Independence he served in the Givati Brigade. He met Sara Levitt Neuman, who was born in 1926 and survived Auschwitz, via mutual acquaintances. They married and made their home in Bnei Brak.

In 1956 Zacklilkowsky was invited by Amichai Feiglin, who served as an operations officer in the Etzel, to work at the oven factory he had established with his father.

"He gathered around him a number of people from the Etzel, and there my father learned the craft of cutting and bending. He became a real expert in the field and his name went before him throughout the area." His expertise would be to his benefit six years later.

Eichmann was born in Germany in 1906, and at a young age he moved with his family to Austria. A few years later he joined the ranks of the Nazi party, returned to Germany, and quickly moved up the ladder, until he was promoted to head of the Gestapo's Jewish Department. His main role was to ensure the implementation of the program to exterminate the Jews – "The Final Solution."

At the end of the war Eichmann was captured by the US Army without them knowing his identity, but he succeeded in escaping. He moved with his family to South America, and ultimately settled in Argentina under the false name "Ricardo Clement." Some 12 years after the end of World War II information began to reach Israel, according to which the senior Nazi officer was living a peaceful life in Buenos Aires.

"In 1957 Eichmann's son began a romance with a young Argentinian woman," says former Mossad man and close friend of Tuly, Avner Avraham. "Eichmann didn't know that the young woman's father was half-Jewish and a Holocaust survivor. When the father realized that it was Eichmann, he passed the information to Dr. Fritz Bauer, who was the attorney general in Frankfurt, and he passed it on to Dr. Felix Shinnar, who was head of the reparations program and managed the negotiations on the issue with Germany. Shinnar was the one who reported this to the Mossad.

"Around a year later the Mossad tried to locate Eichmann, and was helped by the police captain Ephraim Elrom Hofstaedter, who later became the Israeli consul-general in Turkey and was murdered by a Turkish terrorist organization. Hofstaedter came for a conference in Argentina, and after a short examination came to the conclusion that Eichmann couldn't possibly be living in the country. A year later Bauer himself came to Israel, and in a meeting with the head of the Mossad he supplied extra information – a picture of Eichmann with his fake name, Ricardo Clement." Only afterwards, Avraham emphasizes, did Operation Finale begin.

The first to head out to Argentina was the Mossad agent Zvi Aharoni, who reached the Eichmann family home on Garibaldi Street in February 1960 and photographed Eichmann. He sent the pictures for tests with the Israel Police, who determined, according to the ear structure, that it was indeed the Nazi criminal. The Mossad squad that had been sent to Argentina tracked Eichmann and learned his daily movements. On May 11, May 1960 they ambushed him next to a bus stop and captured him.

At the beginning Eichmann stuck by his false name, but during his interrogation, when he was asked his personal number in the SS, he recited the numbers fluently.

On the morning of May 22, 1960, Avraham says, Eichmann was brought to Israel, and his trial began in April 1961.

Like many in the young State of Israel, Zacklilkowsky and his son Tuly also listened to the accusations of the chief prosecutor, Gideon Hausner. Eichmann was found guilty of all 15 counts against him, and in December 1961, over the course of three days, his verdict was read to him. The sentence was death by hanging. The State of Israel decided that, after his hanging, Eichmann's body would be cremated and his ashes would be scattered at sea outside of Israel's territorial boundaries.

In April 1962, five months after the death sentence was handed out, Zacklilkowsky returned home at the end of a day working at the factory, and in his mailbox there was an invitation to a meeting with Naftali Pat, who had formerly served as the owner of the Mafiot Bakery chain. Already during the trial, representatives of the state had approached Pat and asked him to identify a professional who could build an oven the size of the human body.

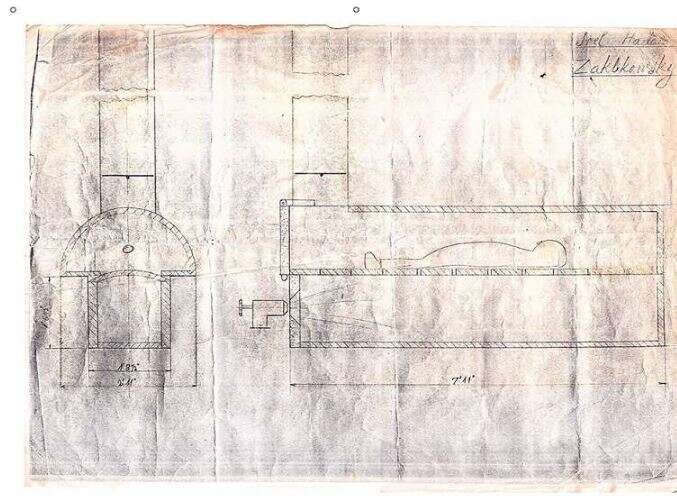

"He was interested to know if I could build an oven with certain specifications," Pinchas says. "I heard the requirements and I said yes." Zacklilkowsky still didn't know what the purpose of the oven was, but when he was told that the oven needed to be able to reach 1,800 degrees Celsius, he understood the meaning of the mysterious request. Apart from him, only three other workers at the factory knew that the oven was designed to cremate Eichmann, including the director Feiglin, and the engineer who designed the oven, Yoel Adar.

For two weeks, Zacklilkowsky labored on building the oven, which was 2.5 meters long and 1.5 meters high. Tuly once said, "he did it in complete silence and in appreciation. Not out of vengeance or because of a grudge. Father built the oven as a citizen and a free person in the State of Israel.

At the end of the two weeks, and after then president Yitzhak Ben-Zvi rejected Eichmann's appeal, the execution operation began. Zaklilkowsky was asked to tell his family that on that day he would only arrive in the morning. "Dad was the most senior worker in the factory," Tuly explains, "he served as the work director and the senior welder. He tested all the ovens that before they left the factory. But the police announced at the last minute that a truck would come to the factory in order to take the oven to Ramla Prison, where the execution would be carried out, and my father didn't have time to check the oven. The first. The first tests he did were really close to the cremation of the body."

The walls of the house of Tuly and Yardena in Shikun Dan in Tel Aviv are decorated with the paintings of Tuly, who became an artist. "These are pictures from the period when I was still normal," he says with a smile, hinting at the personal change he went through. "I have severe ADHD, and over the years painting saved me. After my military service in an anti-aircraft unit, I studied art at the Avni Institute of Art and Design. Among others, I studied with the famous painter Yehezkel Streichman, and I put on all kinds of exhibitions."

At the entrance to the home, just outside his studio, are pictures of his family that perished in the Holocaust. "I escaped from every aspect of the Holocaust, and until recently I didn't know these pictures existed," he says. "Only in 2010, after my mother died, I went to the attic of her home and found the pictures."

Apart from the pictures he also found the item that changed his life. He takes out a large, yellowing sheet of paper with multiple folds, with straight pencil lines sketched on it accompanied by measurements in inches. "This is the sketch of the oven that my father built for Eichmann," he says. "The moment I found it, I felt like my father was telling me: 'You will deal with the Holocaust.' From my perspective it was his will. I felt a kind of religious obligation and I entered into the madness of creation."

The height of Tuly's madness came with a special exhibition of his paintings titled. "The Oven – My Mental Burden," which was curated by Arieh Berkowitz, produced by Avner Avraham, and designed by Levi Tzarfati. From Tuly's perspective, the exhibition, which took place at the start of the year at the Tel Aviv Artists House, was part of his personal journey to make sense of his father's and family's pasts. Alongside the exhibition, Tuly made the film The Oven with his son Noam, which was presented around a month ago at the Tel Aviv Cinemateque's Epos Art Film Festival.

The production of the film, which Tuly also funded from his own money, already began in 2012. "One of my goals was to meet the heroes who took part in the operation to execute Eichmann and cremate his body. I wanted to complete the puzzle that I started to piece together around the building of the oven by my father."

Zaklilkowsky completely rejected the feeling of revenge that might have been natural for him. "There is and never will be anything in the world that can grant atonement or vengeance for the terrible horrors that I experienced or saw during the cursed war," he said. "In building the oven I felt a mission to close a bloody chapter of the Jewish people's history."

After Eichmann's body was taken down from the rope, it was placed in the room where the oven was located. "At six in the evening I did the first test and I turned on the oven," Zaklilkowsky said in the same Yom HaShishi interview. "Yes, he burned nicely." According to him, it was an especially cold night for the season. A few prison wardens and policemen put Eichmann in the oven. "I saw his feet hanging out," he described, "so I took a hoe, pushed him inside, and closed the door. For me it was a major effort."

According to instructions, it was forbidden for Holocaust survivors to take part in the execution of Eichmann, out of a fear that they would take the law into their own hands, but since Zaklilkowsky was the one who built the oven, he was allowed to remain in the room during the cremation and to supervise the whole process.

After the body was cremated, Eichmann's ashes were placed inside a jug, and at 4:30 in the morning it was taken to a boat that was anchored at Jaffa Port. "I was amazed to see how little ashes remained of a person," Goldman says in the film. "At the same moment, I was reminded of my time as a prisoner at Auschwitz. We already knew that there were cremations. When I came close to the [crematorium] building, there was a mountain of ashes and we understood that it was the ashes of human beings. They gave us wheelbarrows, and they told us to fill the wheelbarrows and to scatter the ashes among the paths belonging to the SS officers.

"At that moment, when I stood by the oven, I understood how many thousands of bodies were in the mountain of ashes at Auschwitz. It shocked me. I will never forget that moment. We went to the edge of the boat. We bent over, we turned over the jug and we spilled the ashes onto the waves. That same moment I said, "so shall all the enemies of Israel perish," and someone said 'amen.'"

"In any case dad said something," Tuly adds, "he described how after Eichmann's body had been cremated he left the prison complex, and when he looked back, there in the cold night, with the barbed wire fences of the prison and the ashes rising from the great oven, he was reminded of Buchenwald."

Tuly is currently dealing with Parkinson's disease, which first appeared while he was working on the film. "Until recently I hid my shaking left hand, but recently I decided to stop the deception. Who knows? Maybe I ended this journey at greater peace, both with my father and with Parkinson's," he says with a smile.

Q: Will you continue to deal with the Holocaust in your paintings?

"Yes, it's a subject that's close to me. The craft of painting is suitable for the message that I want to deliver. I don't sign the paintings and I don't sell them. I don't feel that the paintings are really mine. From my perspective, it's not a mission but the work of a lifetime."

Tuly was born in 1952 and was followed two years later by Esther. "Our home was religious in the style of the Mizrachi movement, and I studied at a yeshiva high school," Tuly, who later changed his family name to Ziv, explains.

No comments:

Post a Comment