|

| The Wedgwood arriving in Haifa, 1 July 1946. (Donated to the Clandestine Immigration and Naval Museum, Haifa by Brigadier General Nir Maor/ Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0) |

In the early hours of June 19, 1946, the Wedgwood, a former Canadian naval ship disguised as a banana boat, stole quietly away from Vado on the coast of the Italian Riviera.

But the ship wasn’t carrying fruit; onboard instead were over 1,000 Holocaust survivors secretly bound for Mandate Palestine. Conditions aboard the grossly overcrowded corvette were dire — water was rationed and sanitation poor — and before reaching its destination, the ship would have to run the naval blockade Britain had imposed to impede Jewish immigration.

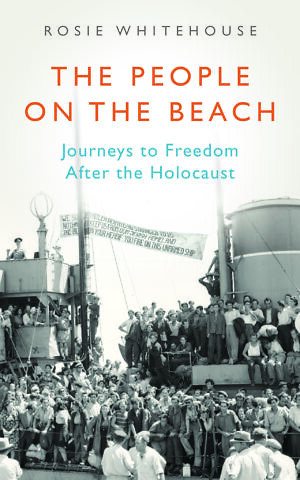

The largely unknown story of the Wedgwood and its passengers is the subject of a new book — “The People On The Beach: Journeys to Freedom After the Holocaust” — by British journalist and author Rosie Whitehouse.

The Wedgwood was just one of many unheralded ships which, in the years between the end of World War II and the creation of the State of Israel, carried thousands of Holocaust survivors from the coasts of the Mediterranean and the Black Sea to Palestine.

After delivering its precious cargo, the flower-class corvette would return to battle, serving extensively as a gunship in the Israeli Navy — including during the 1948 battle for independence — before being retired in 1954.

“This is more than just the story of one boat; it is an account of that biblical exodus,” writes Whitehouse. “It looks at why so many Holocaust survivors felt they could not return to or remain in the places where their families had lived for generations, and how Zionism offered them a future.”

Whitehouse came across a reference to the Wedgwood while updating her travel guide to Liguria in northwestern Italy. That chance discovery sparked a four-year quest to find out how the survivors came to be on the beach at Vado. It took her across Central and Eastern Europe — to Ukraine, Lithuania, Poland and Bavaria — and over the Alps into Italy.

Whitehouse’s journey led her to death camps and the sites of appalling Nazi atrocities. But it also revealed the extraordinary daring, creativity and, at times, sheer chutzpah of those who made possible the Wedgwood’s voyage and that of the countless other ships which ferried the survivors to their promised land. Among them were an American army chaplain, a young doctor who had survived the camps, Jewish Brigade soldiers and secret agents dispatched by the Haganah, the main Jewish paramilitary organization in pre-state Israel.

“This was a massive Jewish rescue mission, Jews saving Jews,” Whitehouse says in an interview with The Times of Israel.

1,300 painful stories

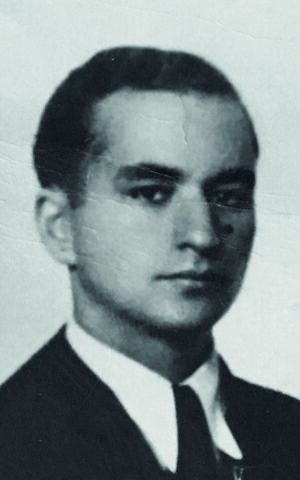

It is the survivors themselves who are at the center of the book. With painstaking research, Whitehouse pieced together a list of the names of the roughly 1,300 people who sailed on the Wedgwood. Most were young — only 21 were over the age of 40 — and two-thirds were men. While they hailed from 14 countries in all, two-thirds were originally from Poland. Many were also former partisans.

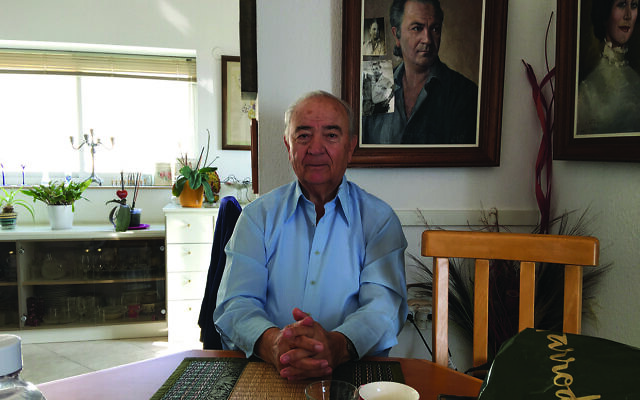

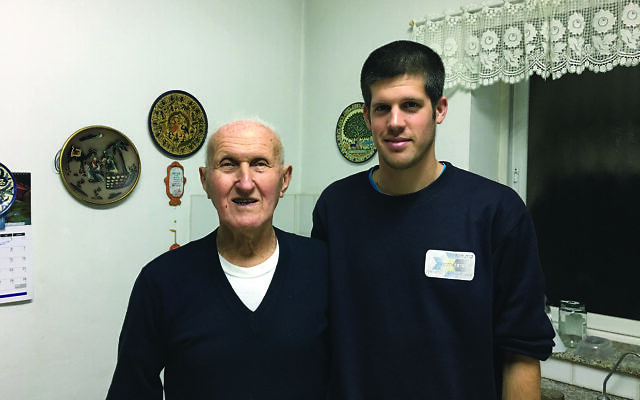

The power of Whitehouse’s book lies in the individual stories of the Wedgwood’s passengers she has gathered. These are stories of the places in Europe they left behind, the barbarity they experienced and witnessed during the war, and their journeys to Palestine. Most are told by the survivors from their new homes in the Israeli cities of Bat Yam, Ramat Gan, Karmei Yosef and Haifa.

“It is an intimate, personal story of the Holocaust, and I believe that is why it matters: it tells the story of the survivors in their own words conveyed to me not in the clinical surroundings of a museum or institute, but in their own homes,” Whitehouse writes. “I believe this is the way the story should be heard.”

Many of the stories are infused with tragedy and pain. Yitzhak Kaplan was 16 years old when he boarded the Wedgwood. He was one of just 3,000 survivors out of the 37,000 Jews who lived in Rivne — a then-Polish city, now in Ukraine — before the war.

While Kaplan, his parents, brother and two sisters fled as the Germans invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, another sister, Fani, opted to wait behind for her husband who was serving in the Polish Army. Fani and her two small children were murdered in a two-day killing spree in November 1941 in which the Nazis massacred 23,500 of Rivne’s Jews in the nearby Sosenki pine forest.

Whitehouse meets Kaplan, a youthful looking 88-year-old, at his home in the hills above Haifa. He tells her that, even after the Nazis had been driven out in 1944, his family soon discovered that Rivne was no longer a safe place for Jews. In early 1945, they made the decision to attempt to get to Palestine.

Alter Wiener has a story which, in some regards, echoes that of Kaplan. He was born in the town of Chrzanow. A 30-minute drive from Auschwitz, its population was half Jewish before the war. The teenage Wiener survived a series of forced labor camps, although he lost most of his family at the hands of the Nazis. After making his way back from Germany to Poland, Wiener arrived at his childhood home.

“I knocked at the front door and told the Polish occupant that I had survived the war, and would like to look at my former home. The man slammed the door in my face,” Wiener recounted to Whitehouse before his death in a road accident in 2018. Later he saw “a little house where the patio was paved with tombstones from the Jewish cemetery.” It was, he said “a painful and shameful sight.” The hostility he encountered convinced Wiener there was no future for him in Chrzanow.

As Whitehouse details, the fear and confusion experienced by Wiener was not unusual for survivors in Poland. Anti-Semitic riots in Krakow in August 1945 saw Jews attacked and beaten, and a woman who had survived Auschwitz lost her life. A year later, blood-libel tales in Kielce sparked a pogrom in which 42 Jews were murdered and 80 seriously injured.

“This is what drove so many of the people on the beach to decide that Palestine was the only future they had,” Whitehouse says.

But Whitehouse, who spent holidays in Eastern Europe as a teenager, says she approached her journey to Poland with “a great tenderness for Poland and for Polish history.” In Kielce, she attempts to find answers as to how Holocaust survivors were being murdered even after their supposed liberation. Bogdan Bialek, a Catholic who now runs a museum and educational center on the site of the Jewish hostel where most of the violence occurred, has spent three decades attempting to get the city to face up to its grim past. He tells Whitehouse that the Nazi occupation had left Poland brutalized and violence normalized. It is an explanation, not a justification, he said. The country, in which so many survivors felt they no longer had a home, had been left “in moral and material ruin.”

The experience of survivors in Poland was replicated throughout Eastern Europe. In the small hilltop village of Karmei Yosef, Whitehouse meets Dani Chanoch, who sailed on the Wedgwood with his brother Uri. Born in Kovno in Lithuania, he is, she writes, “a miracle survivor.” He wriggled free from the grip of a German soldier in the ghetto as the Nazis rounded up children.

“This was the moment that changed me and when I realized that I had to fight to live,” he tells Whitehouse, before recalling how he later survived two selections — held on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur — at Auschwitz. “His comment says much about what formed men like him, the generation who became the first Israelis,” Whitehouse says.

Whitehouse meets another of the Wedgwood’s passengers, poet and writer Moshe Ha-Elion, at his home in Bat Yam. Born in Thessaloniki, he was one of 42 Greek survivors who made the journey to Palestine aboard the ship. His family had volunteered to go to Poland in 1943, believing that it offered the prospect of a better life. In Auschwitz, they were tragically disabused of this notion. “I simply could not believe the Germans could do this,” Ha-Elion tells Whitehouse.

“I can see he is still shocked,” she writes. Like many of the other passengers, Ha-Elion fought in the 1948 war. He went on to serve in the Israel Defense Forces for 20 years and then joined the Defense Ministry. His family’s safety, Whitehouse says, was a priority. “The story of the Wedgwood is also the story of how the survivor in the striped pyjamas became a sun-tanned Israeli soldier with a gun,” she writes.

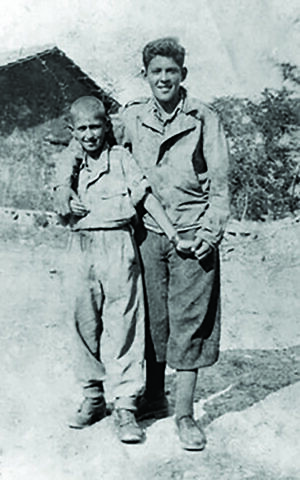

But, as Whitehouse notes, some of its passengers had picked up a gun long before they boarded the Wedgwood. Many had been partisans who had taken up arms against the Nazis and their allies in the ghettos and forests of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union.

“The Jewish resistance that you see during the Holocaust doesn’t stop there,” says Whitehouse. She believes that those who, in the months and years after the war helped the survivors to escape Europe for Palestine, are best viewed as a continuation of it. “It’s resisting all these other things that are being hurled at the Jews,” she says.

Passing the baton

Whitehouse attributes the vision of an escape route out of Europe to Abba Kovner. He escaped the Vilnius ghetto through the sewers and led Nakam, a partisan army, from the forests outside the Lithuanian capital. As well as fighting the Nazis, Kovner’s partisans helped Jews flee to safety.

After the Red Army’s arrival in the city in July 1944, Kovner returned to his family home. A neighbor greeted him with the words: “Are you still alive? We hate you, go away!”

As the Nazis retreated and collaborationist regimes folded, Kovner spent hours poring over maps and papers to ascertain the best way for survivors to get the Black Sea, Adriatic and Mediterranean coasts, and from there to Palestine. But he abandoned his maps and plans and famously set his mind instead to the task of avenging the Shoah by poisoning the water supplies of major German cities.

The task of helping survivors escape from Europe to Palestine fell instead to other Jews. Whitehouse compares the story to “a relay race in which you’re handing on the baton to the next person.” Two crucial players in the first stage were Abraham Klausner, a 30-year-old US army chaplain, and Zalman Grinberg, a doctor and survivor of the Kovno ghetto and the Dachau sub-camp at Landsberg.

Klausner was the first American army rabbi to enter Dachau after its liberation. As Whitehouse describes, he quickly became “the leader and father figure to some 32,000 liberated Jews in and around” the camp. He was, she says, “one of the first people from outside who responds to the survivors.”

Klausner soon discovered that, as he put it in a desperate appeal to American Jewish organizations in June 1945, the survivors were “liberated, but not free.” Confined in a displaced person’s camp, they were subjected to military discipline and lacked food and care.

To help reunite families and friends, Klausner began to assemble a list of survivors — delighting in having it printed in Landsberg, the town where Hitler wrote “Mein Kampf” — and in Munich established an information bureau. In an early edition of his regularly updated and published list, Klausner informed readers that, contrary to military policy, “no Jew need return to his native land.”

Grinberg, in turn, persuaded a sympathetic American officer to allow him, under the guise of being a representative of the International Red Cross, to take over part of a military hospital in the St. Ottilien monastery in Bavaria. It provided a vital lifeline, where Grinberg helped nurse survivors, some of whom sailed on the Wedgwood, back to health.

Less than three weeks after the end of the war, Grinberg staged a concert in the monastery grounds where former camp inmates, some of them members of the former Kovno Ghetto Orchestra, played Mahler, Mendelssohn and other music banned by the Nazis. “This small, seemingly insignificant gathering,” writes Whitehouse, “represented a turning point. It was the first stirring of Jewish self-confidence on German soil.”

At Landsberg, meanwhile, Klausner successfully fought to make the displaced person’s camp all Jewish. Together, St. Ottilien and Landsberg became what Whitehouse terms “hubs of [Jewish]… self-assertion.”

Within weeks, Klausner — again defying his military superiors — established the Central Committee of the Liberated Jews of Germany, of which Grinberg was elected chairman. At its first conference at St. Ottilien in July 1945, delegates voted to demand the establishment of a UN-recognized Jewish state and for Jews to have the right to emigrate to Palestine. The survivors’ Zionism, Whitehouse writes, was “instinctive and not imported from outside.”

Klausner and Grinberg, she explains, “were charismatic leaders in a world where there was very little leadership.” Both had “this incredible eye for the theatrical. They were both great orators, they knew how to rally the people.”

The Jewish Brigade

In June 1945, Klausner had his first meeting with members of the Jewish Brigade. Formed at Winston Churchill’s insistence in 1944, it included thousands of Jewish volunteers from Palestine and mainland Europe. Its soldiers fought the Germans in Italy, but, fearing how the troops might behave once they crossed into the territory of the Third Reich, the British decided the Brigade should be brought to a halt close to the Austrian border in the northern Italian town of Tarvisio. It turned out to be an inadvertently crucial decision, Whitehouse believes — one which would allow renegade young Jewish soldiers to follow their own fast-developing agenda.

In Italy, as one Brigade veteran later put it, the soldiers “began to appreciate the horrors that our people had suffered. Our priority was to rescue those who had survived by any method we could devise.” Thus, in direct contravention of British government policy, they turned Tarvisio into a vital staging post to help Jews — including the Wedgwood’s future passengers — make their way to Italy and thence onto Palestine.

As Whitehouse describes, Klausner became the “the linchpin between the survivors flooding out of Eastern Europe and the Jewish Brigade, which helped them travel on to Italy.” Army trucks driven by Brigade soldiers would travel north into Germany, Austria and beyond, transporting survivors back to Italy to await their passage to Palestine. Some of the children and young people rescued by the Brigade were taken to a former fascist holiday camp near the village of Selvino near Lake Como.

Among their number was 16-year-old Menachem Kriegel, who sailed on the Wedgwood. Kriegel, who Whitehouse met at his home close to the Haifa Zoo, had survived the Nazi occupation of Ukraine by spending 14 months living behind a false wall. Another group of teenage boys who were later passengers on the Wedgwood were taken to the Villa Bencista, which lies in Fiesole in the hills above Florence. It was run by a Jewish Brigade soldier, Arie Avisar. “He taught us to be people,” Yechiel Aleksander tells Whitehouse when she meets him at his home near to Binyamina.

Aleksander highlights the crucial impact the Jewish Brigade troops had on the youngsters they helped to Italy. “We were out of control,” he says of a group he hung out with after their liberation from the camps. “We did not listen to anyone until one day soldiers from the Jewish Brigade came and saved us.”

In what Whitehouse calls the “Wild West of recently liberated Europe,” young teenage survivors often had nobody to look after them. “They had already been living feral lives in the ghettos,” she says. “It was only the Jewish Brigade that they were going to respect.”

Ha-Elion recalls spotting for the first time a convoy of Brigade trucks making its way through the Austrian countryside. “The soldiers had little signs on their arms that had the same Star of David on,” he tells Whitehouse. “I realized they were Jews and it was a wonder.”

Their work with the survivors also helped to sate the anger and rage which the soldiers understandably felt. “The Jewish Brigade [were] on a very dangerous knife edge and it does give the young soldiers a purpose,” Whitehouse says.

‘The Gateway to Zion’

Whitehouse dubs Italy “The Gateway to Zion” with some 70,000 survivors traveling through the country between 1945 and 1948. “I think it does tell us something very positive about Italy,” she says. “The ordinary people were extremely friendly to the survivors.”

A remarkable cast of characters were responsible for the successful journey the Wedgwood’s passengers — and many other survivors — made through Italy and on to Palestine. Raffaele Cantoni, a Jewish socialist and anti-fascist, had been a leading light in various Italian organizations which sought to assist Jewish refugees before the war. He also helped establish a network which helped Italian Jews after Mussolini’s anti-Semitic laws took effect in the late 1930s.

“Cantoni jumped from a train on the way to Auschwitz,” says Whitehouse. “This man is almost kind of unstoppable.”

A prodigious fundraiser and a member of Italy’s National Liberation Committee, the umbrella organization for the resistance groups which fought the German occupation, Cantoni reactivated his network after the war to rescue the survivors. As well as being responsible for the young survivors being housed and cared for at Selvino, he also set up a reception center in a 16th-century palace in Milan. In the two years after it opened, 35,000 survivors including Kaplan and other Wedgwood passengers found food, assistance and temporary shelter behind its doors.

But it was two rather shadowier characters — Yehuda Arazi and Ada Sereni — who were chiefly responsible for the crucial, final leg of the Wedgwood passengers’ journey. Code-named Alon, Arazi was a founding member of the Haganah who was secretly smuggled into Italy by a Polish aircrew in 1944. He quickly made contact with Cantoni and the Jewish Brigade at Tarvisio and began organizing the illegal emigration of Jews to Palestine.

Sereni, the daughter of one the richest Italian Jewish families, had emigrated to Palestine with her husband, Enzo, in 1929. He, though, had died at Dachau in November 1944 after being parachuted into Italy and captured by the Germans. Months later, Sereni arrived in Italy to complete her late husband’s mission of helping Jews escape to Palestine. “One thing that I was struck by as I was doing the research for this story is that it’s full of incredibly strong and powerful women,” says Whitehouse.

Arazi and Sereni formed what Whitehouse terms a “dynamic duo,” with more ships departing from Italy for Palestine on their watch — 56 in all — than any other European country. Sereni’s contacts, including with the Italian authorities, proved invaluable. So too did her ability to help Arazi weave together a series of deals with merchants, ships and shipyard owners, and those whose cash would finance the operation.

In the late summer of 1945, the British caught on to the Jewish Brigade’s activities and moved it out of Italy. Some soldiers passed their uniforms and papers to survivors with whom they shared a passing resemblance, allowing them to be shipped back to Palestine courtesy of British carriers. These Brigade members then joined Haganah agents in Arazi’s most audacious creation — a “phantom platoon” with the equipment, papers and kit to pass itself off as a genuine army unit.

Headquartered in Milan, Arazi’s “Gang,” as they came to be known, ferried survivors from Central and Eastern Europe to Italy, picking up the necessary “supplies” for their journeys from Allied bases. Many British troops in Italy, believes Whitehouse, were well aware of this subterfuge and chose to turn a blind eye.

Just outside the town of Magenta, west of Milan, Cantoni helped Arazi and Sereni secure the use of a former partisan hideout. The small secluded villa and its grounds became “Camp A,” the logistical hub of the operation, where everything necessary to rig out a ship — together with weapons which were being smuggled to Palestine — were prepared and stored. Aleksander and former partisans Fedda Lieberman and Lea Diamant worked at the camp before joining the Wedgwood for its journey across the Mediterranean.

A journey into the unknown

The Wedgwood, named after Josiah Wedgwood, a pro-Zionist British Labour parliamentarian who had championed the cause of Jewish refugees until his death in 1943, was a former Canadian naval ship. It was purchased as part of an operation backed by American sympathizers and run by a senior Haganah official in the US, Zeev Shind.

Crewed in part by young Jewish American volunteers — most of whom had no experience at sea — it left New York in April 1946. After stopping in the Azores, it arrived in the Italian port of Savona a month later, where, under Arazi’s watchful eye, it was refitted with bunks and hammocks. As it prepared to make its way to Vado, the Gang, driving a fleet of British Army trucks, set off to collect two groups of survivors from Genoa and Tradate.

For the survivors, though, there was to be one, final heart-stopping moment when the Italian police arrived at the beach just as the Wedgwood sailed up to the jetty. While Arazi and Sereni were taken away for questioning, the offer of American cigarettes convinced the police to allow the Wedgwood’s passengers to board and the ship to depart.

The Wedgwood managed to reach international waters without attracting the attention of British warships, but it was inevitably spotted as it passed Cyprus and headed for the coast off Tel Aviv. Three Royal Navy destroyers were dispatched to intercept the boat. Warning shots were fired and, after a 14-hour stand-off, the crew disabled the engines and the navy towed the Wedgwood into Haifa. As the British prepared to board the boat, its passengers gathered on the deck and sang the soon-to-be Jewish state’s national anthem, “Hatikva.”

Few of survivors, says Whitehouse, had any idea that what now awaited them was a stay in the Atlit detention camp. It was an inauspicious start and, for many, the first of a series of challenges.

“I think they found life very difficult,” she says. “The rules of Israeli society were starkly different from those that they had grown up with.”

But, Whitehouse says, this is to miss the bigger picture. Instead, the feelings of most of the Wedgwood’s passengers are captured by 95-year-old Yehuda Erlich when she meets him at his bungalow in Ramat Gan. “I had no regrets ever about coming here,” Erlich tells her.

THANKS SO MUCH,, IT MEANS THE WORLD TO US IN THESE DIFFICULT TIMESֱ

blah blah blah

ReplyDeleteread Perfidy by Ben Hecht

that is the toned down version

the leaders of Israel were partners in crime with the Nazis

You can't rewrite history by focusing on one boat

2:28

ReplyDeleteWow wow wow ....there are still frum Jew out there believibg the Satmar lies and propaganda... .....

My own grandfather and two uncles were on one of those boats ...

2:28

ReplyDeleteWhich leaders were in crime with the Nazis?

You mean Rudolf Kastner the Zionist who saved the Satmar Rebbe's life ...?

The Book that Ben Hecht wrote, Perfidy, the Satmer Bible, was about the trial of Kastner ..

Ben Hecht himself ...the Satmar Idol, was married twice in his life , both to shiksas and fathered two children both goyim...

Hecht started out being a self-hating Jew and wrote a book where he called Jews "sons of pigs"

Hecht later became a fervent Zionist after meeting Peter Bergson the money man for the Irgun ...the Irgun was founded by Jabotinsky and Menachem Begin was one of the founders and leaders...no heroes of Satmar ..

Bergson hated Ben Gurion and his party because Ben Gurion was more of a pacifist against the British ... whereas the Irgun was for open warfare ...in fact Hecht wrote an open letter to the Jewish insurgents openly praising underground violence against the British

When Kastner was called a "nazi Collaborator"by a small newsletter, the Israeli Government sued the author of that newsletter for libel....the book "perfidy" is the story of that trial ... in that Trial the initial verdict was that Kastner was in fact a collaborator, but after the trial, new evidence emerged from actual Nazi Archives proving that Kastner was in fact not a collaborator but was negotiating with the Nazis to save Jews which he subsequently did ... saving the life of the Satmar Rebbes, his Gabbai, Yosef Ashkenazi, and the life of Esther Yungreiz and her entire family ..

at the second trial where new evidence was presented including hundreds of hours of testimony, many from frum Heimishe Yeeden, Kastner was in fact acquitted, but it was too late for Kastner since he was murdered two weeks before learning of the final verdict

Hecht wrote that book to embarrass Ben Gurion , it wasn't written against the Zionists since Hecht at this time was a big Zionist supporter .... but in retrospect Ben Gurion was probably correct and because of his foresight we have a beautiful country that houses close to 6 million Jews ...

To say as you did "bla bla bla... making light of the Zionist contribution for saving European Jewry proves that you are an ignorant brainwashed fool!

The zionist are first at saving Jews as we saw in Entebbe .. and in hundreds of other cases ... it's a country unlike Monroe ,that takes in all Jews whether it be Satmar, kloizenberg, Neturei Karta, Dati, Mizrachist , Iraqui, Morroccan etc etc ...

Saving one life is considered according to Chazal as saving the entire world,,, how much more so hundreds of thousands... and the Zionist saved the life of the person stabbing them in the back ... the Satmar Rebbe who was asked to give a letter on behalf of Kastner at that trial, which he refused to do........

those are the facts ...

to even think that a Nazi would collaborate with a Jew is so crazy and stupid... but when you hate other Jews because they are Zionists then everything makes sense..

to Bla Bla Bla

ReplyDeleteSo you are upset that the Zionists collaborated with the Nazis to save your Rebbes derriere ??

Attention bla bla.... it was the Zionists in Europe were most active in hatzalah and many sacrificed their lives to save Jews..In Hungary , for example.. Read Operation Hatzalah , by Gilles Lambert... How young Zionists recued THOUSANDS of Hungarian Jews..

ReplyDeleteKasztner himself started his efforts by helping Polish and Slovakian Jews..

Perfidy , has been destroyed by critics..

The prosecutor Tamir was also a Revisionist who hated the Mapai Party..

Not a SINGLE accusation against the Zionists was proven in court. Justice Halevi was also an anti-Mapam judge.

The problem with bka bla and his ilk is that they never read books, only Goebbels propaganda..

Again : Despite their lies , Kasztner saved their rabbi.. !!!!!!!!!!!

the Derby , en route..

Oh, did I mention that Kasztner saved their rabbi ??

Yes, I did.

Hey bla bla , Can you guess who ??...

ReplyDeleteZionists were working a certain city in Romania-Transylvania to help Jews leave and bring them to EY.

A certain rabbi not only forbade his people to speak with them but threw a cheirim .These are from sworn affidavits by survivors right after the war.. Your Shytt'eh ain't cutting it anymore.

Cha Cha de Chazzente

It's worth reading eminent historian Lucy Dawidowicz's destruction of Perfidy in a Commentary magazine article of March , 1962. It's online for all to see.

ReplyDeletehe Derby

Bla bla Bla

ReplyDeleteThe impetus for Kastner's dealings with the Nazis in the first place was the fact that Dieter Wisliceny, Eichmann's envoy, had arrived in Budapest with a letter of introduction from Rabbi Michael Dov Ber Weissmandel. The Slovakian Orthodox leader had been bribing the Nazis with money to stop deportations.

So would you admit that Rav Weissmandel collaborated with Nazis? Because the facts are that he did...

The true villains of the Shoah, let us never forget, were the Nazis and their enablers who barred the gates of refuge

No Satmar Shitah will or can change those facts .... the Zionist Founders, though not perfect, provided a home for hundreds of thousands survivors .... those who choose to twist the facts and re-write history peppered with Talmudical sayings are evil and ungrateful....

Am Yisroel Chai ...